Written By Ashish Kumar Srivastava

The January 2025 Palisades and Eaton wildfires devastated communities across California and pushed the insurance market to a defining crossroads—testing whether the industry can still underwrite climate risk in its current form.

Executive Summary

January 2025 Palisades and Eaton wildfires have become a watershed moment for the insurance industry. With nearly 30 lives lost, more than 200,000 residents displaced, and upwards of $20 billion to 30 billion in insured losses, these fires now stand as the costliest wildfires in U.S. history. Their significance, however, extends far beyond the financial toll. They have tested the resilience of re/insurers, strained public backstops such as California’s FAIR Plan, and revealed the widening gap between the risks communities face and the protection they can realistically afford.

This disaster is not an anomaly. It reflects a broader pattern of escalating catastrophe losses driven by climate change, urban expansion into high-risk zones, and the rising value of assets in harm’s way. While U.S. carriers remain well-capitalized and global reinsurers have so far absorbed these losses without destabilization, the industry’s reliance on reactive risk-transfer models is no longer sufficient. The wildfires underscore that the challenge is not whether insurers have the capital strength to pay claims today; the challenge is whether insurance underwriting, pricing, and portfolio management can adapt quickly enough to anticipate tomorrow.

The story of the 2025 California wildfires is therefore about more than destruction. It is about the urgent need for a new paradigm in insurance—one where insurance underwriting becomes more granular, mitigation requirements are embedded into coverage, capital markets assume a greater role in absorbing tail risk, and resilience is treated as a core feature of every community. If the industry can rise to this challenge, California’s tragedy may become a catalyst for transformation. If it cannot, the event may be remembered as the moment when parts of the country began to slip toward uninsurability.

Historical Context of California Wildfires

California has long been the global epicenter of wildfire risk, but the events of 2025 represent a scale and severity that even the state’s troubled history rarely anticipated. Earlier disasters such as the 1991 Oakland Tunnel Fire, the 2017 Tubbs Fire, the 2018 Camp Fire, and the 2023 Lahaina Fire in Hawaii were all considered defining catastrophes. Yet all of these have now been eclipsed by the Palisades and Eaton wildfires, which together are expected to result in insured losses exceeding $20-30 billion (Exhibit 1). Average annual wildfire losses have shifted dramatically over the past decade, rising from about $1 billion in the early 2010s to between $3 and $5 billion in the early 2020s. The January 2025 events alone will surpass $20 billion, illustrating how climate change, urban expansion, and asset growth in high-risk zones magnify every acre burned.

Exhibit 1 – U.S. top wildfires losses in the past 10 years, $B of losses (Source: Aon, Reinsurance News)

Anatomy of the 2025 Wildfires

The January 2025 wildfires were, above all else, a crisis for homeowners. More than 85 percent of the losses were concentrated on residential lines, while only 15 percent fell on commercial exposures. This placed disproportionate stress on personal lines carriers and heightened reliance on the California FAIR Plan, which by late 2024 had already accumulated $458 billion of exposure. With coverage caps of $3 million for personal property and $20 million for commercial property, many policyholders will find themselves significantly underinsured. The destruction was staggering: the Palisades Fire destroyed 6,834 structures, while the Eaton Fire razed 9,418. Together they now rank among the most destructive wildfires in the history of California. It is worth noting that wildfires represent a small portion of overall losses to the property insurance market (Exhibit 2); however, the recent growth trend is commanding renewed scrutiny from underwriting and risk-capital committees.

Exhibit 2 – Share of insured losses by peril type by decade, and 40-year average (Source: Swiss Re)

Systemic Challenges Exposed

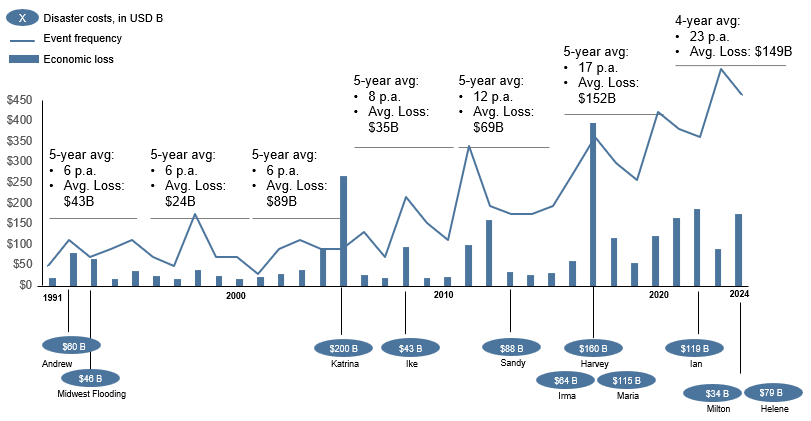

The wildfires expose several structural weaknesses in the insurance model. The accelerating frequency and severity of climate-related losses is one. In the 2000s, the United States averaged seven billion-dollar disasters annually. Between 2020 and 2024, that figure more than tripled to twenty-three, with average annual losses exceeding $150 billion (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3 – The Escalating Frequency and Cost of Billion-Dollar Disasters in the U.S. (Source: National Centers for Environmental Information, NOAA)

Another challenge is the protection gap. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. homes are underinsured, up from 55 percent in 2013. Thousands of families in southern California will now discover, as survivors of the 2021 Marshall Fire did before them, that their coverage is inadequate to fund reconstruction.

Affordability pressures are also compounding nationwide (Exhibit 4). Homeowners’ insurance premiums rose by 10.4 percent in 2024, following a 12.7 percent increase in 2023. Thirty-three states experienced double-digit increases, with Nebraska leading at 22.7 percent. Major national carriers including American Family, Liberty Mutual, and Progressive implemented companywide hikes ranging from 13 to 17 percent, with certain states seeing increases of more than 40 percent. For households, the steady pace of double-digit premium hikes has become the equivalent of a second mortgage layered onto already stretched budgets.

Exhibit 4 – U.S. Homeowners Insurance Rate Changes and Loss Ratio (%) (Source: S&P)

California’s experience illustrates a different facet of this affordability challenge. Regulatory oversight has historically constrained carriers from filing large rate increases, which means California does not appear among the top states for double-digit hikes. But instead of high rates, the state faces shrinking availability. Major national carriers have curtailed or withdrawn entirely from the market due to wildfire exposure and pricing constraints, leaving the FAIR Plan to absorb displaced risk. By late 2024, FAIR Plan exposure had nearly doubled since 2018, reaching $458 billion. In California, the crisis is therefore one of availability as much as affordability, with households in high-risk zones struggling to secure adequate coverage at any price.

The Capital Markets and Ratings Lens

From a capital markets perspective, the wildfires created both stress and resilience. For most carriers, the event represented between three and four percent of their total California property premiums. S&P Global had embedded $90 billion of catastrophe load into its 2025 combined ratio forecasts, and the wildfires consumed about 11 percent of that allowance. Global reinsurers entered 2025 with strong capital positions after record earnings in 2024, and disciplined attachment points shielded them from excessive frequency losses. Catastrophe reinsurance pricing, which peaked in 2023, moderated slightly in the January 2025 renewals, but reinsurers defended their terms and conditions. The implication is clear: traditional reinsurance alone will not suffice. Greater reliance on insurance-linked securities, catastrophe bonds, and other capital markets solutions will be needed to diversify risk. These figures underscore that the issue is not capital adequacy but systemic adaptability

Paradigm Shifts in Insurance

The fires of January 2025 accelerate paradigm shifts that were already underway. Insurance underwriting is moving from ZIP-code based models to parcel-level analytics integrating geospatial imaging, climate data, and hazard monitoring. Mitigation, once encouraged through premium credits, is becoming a prerequisite for coverage. Public backstops such as the FAIR Plan and the excess and surplus lines market will absorb displaced risk, but their adequacy will depend on new approaches to capitalization. Capital markets are becoming more deeply integrated, with catastrophe bonds and parametric instruments providing tail-risk protection. Resilient construction is being reframed as a value driver rather than a cost burden, delivering substantial returns through avoided losses. Finally, claims management is undergoing modernization on a scale, with artificial intelligence, automated triage, and vendor networks enabling faster and fairer recovery.

Conclusion: A mandate for reinvention

The January 2025 wildfires were not an anomaly; they were a preview of what lies ahead if the insurance industry fails to adapt. These events have pushed the sector to a structural turning point where incremental adjustments and legacy frameworks are no longer sufficient. For years, capital strength was the primary measure of an insurer’s resilience, but that is no longer the defining constraint. The central challenge now is whether the industry can evolve its imagination and technical sophistication at the pace demanded by climate volatility. California’s tragedy will be remembered as a catalyst for transformation only if insurers, regulators, capital markets, and communities shift from covering legacy risks to engineering future resilience.

This path forward demands urgent, bold alignment. Insurers must lead by reinventing their underwriting, moving from outdated ZIP-code-based averages to hyper-local, dynamic models grounded in climate science and real-time data. Coverage must be directly linked to demonstrable mitigation, making resilience a prerequisite, not just an option encouraged by premium credits. This new approach must be supported by regulators, who face the difficult task of balancing consumer protection with market solvency to address the crisis of availability that plagues states like California. A reimagined and adequately capitalized FAIR Plan, alongside new public-private resilience funds, will be essential to this effort.

At the same time, the traditional reinsurance market cannot solve this problem alone. Capital markets must expand their role in absorbing tail risk by mainstreaming instruments like catastrophe bonds and parametric triggers. This financial innovation must be paired with physical changes in our communities. Resilience must become the foundation of sustainable housing and insurance availability, embedded into building codes, zoning restrictions, and construction standards. When resilient construction is reframed as a value driver delivering returns through avoided losses, it reinforces the entire system.

The lessons from California are a global warning, echoing in Australia’s bushfires, Canada’s wildfire seasons, and across the Mediterranean. Entire geographies risk becoming uninsurable unless the industry pivots from reacting to disasters to designing ahead of them. The stark question now is whether the industry will lead this redesign of resilience or be left responding, again and again, to disasters it could have prevented.