Public pressure over affordability is reshaping how Europe evaluates investment migration pathways.

WASHINGTON, DC

Spain has ended its real estate-linked golden visa route, closing a chapter that began in the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis and ends in a very different political climate, one dominated by housing affordability, tenant anger, and a growing belief that residency incentives can spill into local markets even when they target a small group of wealthy buyers.

The government framed the move as a housing measure, not an immigration adjustment, saying it would stop granting investor residence permits tied to large property purchases and eliminate investor residency visas more broadly. The official announcement setting out the change and its effective date is published by the Spanish government here: La Moncloa statement on the end of the Golden Visa.

For investors and their advisers, the closure is less about Spain alone and more about what Spain’s decision signals. Across Europe, investment migration pathways are increasingly evaluated through the lens of domestic politics. When housing becomes the defining issue in elections, the idea of rewarding capital with a streamlined status route becomes a convenient target, even if officials privately acknowledge that affordability is driven mostly by supply constraints, wage stagnation, tourism demand, and years of underbuilding.

Spain’s move also changes how the market prices “European optionality.” The golden visa pitch always leaned on a simple promise: buy an asset, get a legal foothold, keep mobility open. In 2026, that promise is weaker, not only because some programs are closing, but because public pressure is pushing governments to reframe investment migration as a contributor to inequality, not just a tool for attracting funds.

The policy shift was telegraphed by the politics, not the paperwork

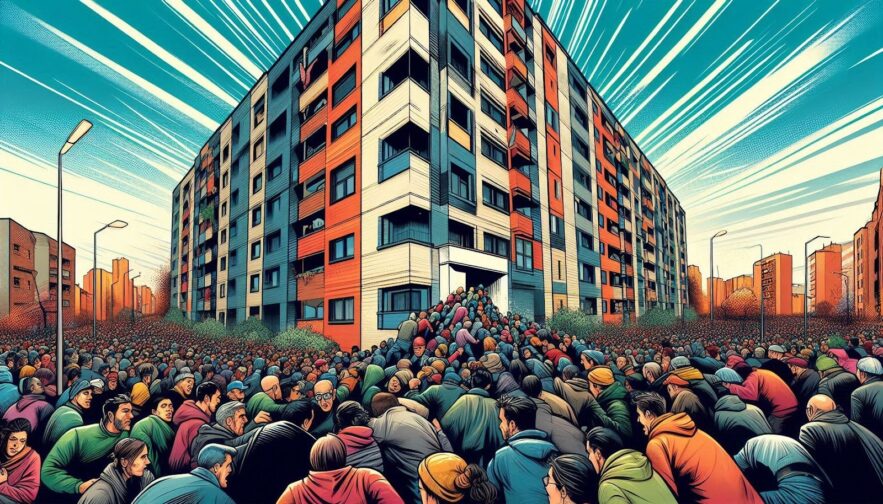

Spain’s housing debate has been boiling for years, but it reached a new intensity as rents rose, first-time buyers struggled, and local protests expanded from city centers to tourist-heavy neighborhoods. Housing politics now shapes national policy in the same way inflation or unemployment once did, as a headline issue that can make or break a coalition.

In that environment, the golden visa became a symbol. It was easy to explain, and it carried a built-in narrative contrast: locals struggling to rent while wealthy foreigners could fast-track residency by buying homes. The actual scale of the program is secondary to the story it tells.

That matters because politics tends to resolve symbolism faster than it resolves structural problems. Ending a visa category is quick. Building housing stock is slow. Tightening landlord regulation is messy. Reforming zoning is contentious. So, governments often lead with the action they can execute immediately, and then promise longer-term solutions later.

Spain’s messaging followed that pattern. It presented the closure as a way to reduce pressure in “high tension” markets, particularly in places where prices have outpaced local incomes. Even if the program represented a small slice of overall transactions, policymakers argued it was one slice the government could control.

Why real estate became the line in the sand

Investment migration programs come in many forms, from bonds to venture investment to jobs creation. Real estate has always been the politically vulnerable category for a simple reason: housing is not a luxury good in the public mind. It is a basic need.

When a residency incentive is tied directly to housing, the program is easier to frame as a conflict between capital and community. It becomes a story about who gets to live in a city, who gets priced out, and who is seen as benefiting from policy.

Real estate also produces visible symbols. Luxury units held as second homes. Empty properties in prime neighborhoods. Agents marketing neighborhoods as “investment zones.” Even when these effects are anecdotal, they are potent. Politicians respond to what voters can see.

Spain’s decision, therefore, fits a broader European trend: treat housing-linked routes as the most politically toxic form of investment migration, even while leaving other mobility pathways, including work, entrepreneurship, and residence-based routes, intact.

The compliance angle: the golden visa brand is now an enforcement story

Even when the public debate is framed around housing, the enforcement debate sits underneath it. European institutions and partner governments have spent years warning that investor routes can create vulnerabilities in identity assurance, sanctions compliance, and background checks, especially when programs prioritize volume and speed.

The key point is not that most applicants are problematic. The point is that a small number of bad approvals can create outsized damage, and unwinding those approvals later is hard.

Once residency is granted, it often becomes renewable. Once a person builds a life around that status, the legal and reputational cost of revocation rises. Governments learn quickly that the true risk is not approval, it is reversal. That is why some policymakers prefer to end routes entirely rather than defend and reform them under constant scrutiny.

The golden visa label has also become politically radioactive because it is now closely associated, fairly or not, with the idea of buying around rules. In a post-sanctions world, that framing is powerful. It lets opponents argue that any streamlined route might be exploited by people seeking to obscure identity histories or bypass ordinary screening friction.

Spain’s closure should be read in that context. Housing was the public justification. Trust and risk were the underlying vulnerabilities.

What happens to people who already hold Spanish investor status

Closures tend to raise a single urgent question: what about existing holders.

Spain’s official communications indicate that the change is aimed at stopping new grants under the investor route. In most policy closures of this kind, existing permits are typically allowed to remain valid and renewable under transitional rules, but renewals can become more technical and more scrutinized, especially if the broader program architecture is being dismantled.

That is where uncertainty appears in practice. A permit holder may still be legal, but their status becomes a “legacy product” in a system that no longer wants new entrants. Banks ask more questions. Landlords ask for clearer proof of legal residence. Travel becomes more sensitive to document details. People feel the friction even when the rules still allow them to stay.

For families, the practical risk is administrative rather than dramatic. It is more appointments, more paperwork, and more effort to prove continuity. Anyone who structured long-term plans around a program that is no longer politically defensible should assume the system will become less forgiving, not more.

Investors are being pushed toward slower, more lived-in pathways

The Spain decision will not end interest in European residence. It will redirect it.

In 2026, the paths that appear most durable are those that look like real migration, not transactional status acquisition. That includes routes built around employment, entrepreneurship with credible operations, study leading to longer-term status, family links, and longer residence-based naturalization.

It also includes newer categories that governments can frame as “productive” rather than “extractive,” such as digital worker residency in some jurisdictions, when paired with tax compliance and local spending.

This is not only a moral shift. It is an optics shift. Politicians want to be able to say a newcomer contributes through work, taxes, and community participation. It is harder to sell the story of a newcomer contributing primarily through a property purchase, especially when housing is the main political wound.

Advisers in the mobility space increasingly frame this as a pivot from price to patience. A residency route with time requirements may be less attractive to the purely transactional buyer. It can be more attractive to the person seeking long-term stability, because it is harder for politics to unwind a pathway that is built on genuine connection.

Housing politics is now a regional force, not a local one

Spain’s decision also reinforces a broader pattern. European countries do not evaluate these programs in isolation. When one government ends a housing-linked golden visa, it becomes a reference point for others.

In political communication, there is safety in alignment. Leaders can say, in effect, this is not an unusual move; others are doing it too. That line helps neutralize criticism that a government is acting rashly or ideologically. It also creates a domino effect, where programs become vulnerable because they are associated with a category that is now under suspicion.

The same dynamic affects cities. When residents in one market see policy action in another, they demand it at home. Housing activism is increasingly networked. The pressure travels.

For a quick sense of how the story is being framed across outlets and jurisdictions, see the rolling coverage and headlines gathered here: latest reporting on Spain ending the golden visa.

The market impact: the myth of “guaranteed access” keeps collapsing

The golden visa era thrived on one implicit promise: regulatory stability. Investors were told the rules might evolve, but the route itself would remain open, and the benefits would remain recognizable.

That assumption is weaker now.

Housing politics changes fast. Security politics changes faster. When a government decides a program is politically costly, it can move quickly, sometimes with short transition periods. That is true even in countries with strong rule of law, because rule of law does not mean programs never end, it means they end through law.

The immediate market reaction is predictable. Short spikes in last-minute filings. Agent’s marketing “final window” packages. Buyers rushing to close property deals to qualify. Then a steady reorientation toward alternative jurisdictions or alternative categories.

The longer-term effect is more subtle. Investors and advisers begin to treat policy risk as central, not peripheral. They stop asking only, what does this route offer today. They ask, what will this route look like when politics turns.

What “responsible” investment migration looks like after Spain’s decision

Spain’s closure will intensify the debate about what, if anything, should replace housing-linked investor residency.

Some policymakers will argue the entire concept is flawed. Others will argue it can be made defensible if it is tied to productive investment, meaningful presence, and transparent screening.

In practice, the models that survive scrutiny tend to share a few traits.

They prioritize identity assurance over speed, including deeper background checks and cross-database verification.

They require real physical presence that creates an evidence trail of connection.

They produce economic activity that is legible to voters, such as business formation, job creation, or investment into productive sectors, rather than simply bidding up scarce housing stock.

They create clear mechanisms to pause, review, and revoke approvals in cases of misrepresentation, without turning revocation into a political spectacle.

They communicate benefits to the public in a way that looks like fairness, not privilege.

Spain’s move suggests a blunt conclusion. If the public cannot see the benefit, and can easily see the downside, the program will not last.

What applicants should do now if they are pursuing Europe for lawful residence

For individuals considering any investment-linked pathway, Spain’s decision offers a practical checklist, not a moral lecture.

First, treat housing politics as part of your risk assessment. If a country is in the middle of an affordability crisis and public anger is rising, assume policy will tighten.

Second, build your plan around continuity, not a single document. The strongest mobility plans are the ones that remain coherent across residence, tax compliance, banking, and travel behavior.

Third, prefer pathways that require time, presence, and real-life ties if you want durability. Transactional routes are politically fragile.

Fourth, assume future scrutiny will be higher than past scrutiny. Programs can improve due diligence today, but the reputational damage from yesterday’s approvals can still shape tomorrow’s restrictions.

Professionals who advise on compliant cross-border planning often emphasize that the winning approach in 2026 is the one that can be explained, calmly, to a skeptical bank, a skeptical border officer, and a skeptical journalist. That is the lens applied by Amicus International Consulting, which focuses on lawful mobility planning that holds up under modern screening standards, including documentation integrity and long-term compliance discipline.

The bottom line

Spain’s decision to end the real estate golden visa is not only a migration policy story. It is a housing story, a legitimacy story, and a warning about how quickly the politics of affordability can reshape mobility incentives.

Europe is not closing its doors to newcomers. It is redefining what kinds of newcomers it wants to reward, and what kinds of pathways it can defend in public.

In 2026, the old golden visa narrative, buy an asset, get a foothold, keep the benefits stable, is giving way to a new one. If you want European residence to last, it needs to look like real residence, not a receipt.