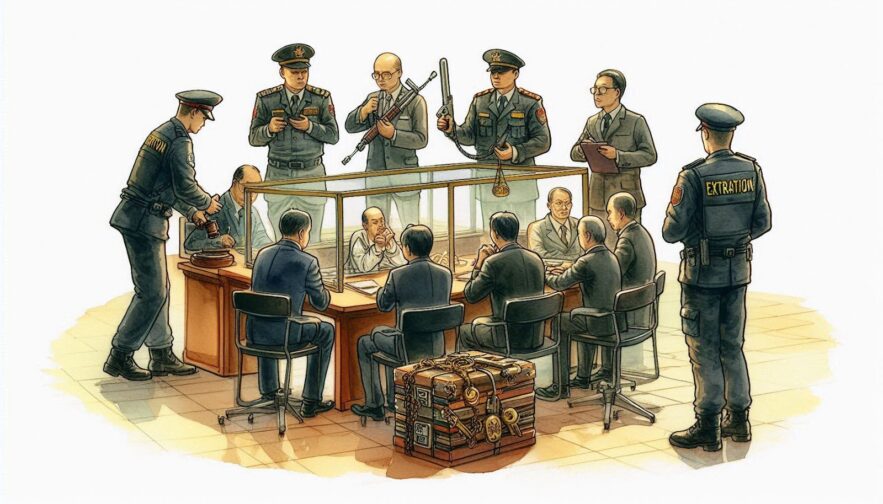

VANCOUVER, British Columbia, September 17, 2025 – Extradition is often portrayed as a straightforward process: one country asks, another country complies, and fugitives are returned to face justice. The reality is far more complicated. Among the most enduring and controversial barriers in international law are nationality bars. In many countries, constitutional or statutory rules prohibit the extradition of citizens, creating legal and political safe havens for those who fall under suspicion abroad.

For the United States, which maintains extradition treaties with more than 100 countries, nationality bars pose both a practical and diplomatic challenge. They slow prosecutions, shelter fugitives, and force American authorities to adopt creative workarounds to ensure that justice proceeds even when surrender is impossible. This release examines the origins of nationality bars, the jurisdictions that enforce them, the safe havens they create, and the strategies employed by the U.S. Department of Justice to counter them. Case studies demonstrate how theory is applied in practice.

The Legal Foundations of Nationality Bars

Nationality bars trace back to principles of sovereignty and loyalty. Many states view surrendering their own citizens to foreign courts as a betrayal of the social contract. Constitutions in Brazil, France, Germany, and Russia all contain provisions that prohibit or restrict the extradition of nationals. These protections reflect both historical and political considerations.

In Europe, where governments are sensitive to human rights obligations, courts often argue that citizens should be tried in their home countries under familiar legal protections. In Latin America, bars stem from traditions of nationalism and suspicion of foreign influence. In authoritarian states, nationality bars serve as shields for political allies and instruments of defiance against adversaries.

Treaties reinforce these constitutional positions through numerous bilateral extradition agreements explicitly exempt citizens from surrender, leaving the prosecuting state with limited options. Even where treaties do not contain express bars, domestic courts often interpret national law to prohibit the extradition of citizens. This means that U.S. prosecutors must accept a legal landscape where cooperation is the norm for foreign nationals but not for citizens.

Safe Havens: Where Nationals Are Shielded

The result of nationality bars is the creation of safe havens. Fugitives aware of their protections often return to their home soil as soon as investigations begin. Brazil has long been a prominent example. Its constitution prohibits the extradition of nationals except in cases involving narcotics trafficking under specific conditions. Brazilian courts regularly deny U.S. requests to surrender Brazilian citizens, insisting instead on domestic trials.

Germany and France likewise refuse to extradite their nationals, though they have become more willing to prosecute them domestically based on evidence provided by allies. Russia takes a different approach, categorically refusing to surrender its citizens regardless of the crime. For high-profile fugitives such as Edward Snowden, this stance has made Russia a last resort haven.

Safe havens present multiple challenges. They embolden fugitives, frustrate victims, and undermine deterrence. They also complicate diplomacy, as governments must explain to domestic audiences why suspects remain free abroad. For the U.S., which prides itself on long-arm jurisdiction, nationality bars are among the most stubborn obstacles to enforcement.

U.S. Workarounds: How Prosecutors Adapt

Faced with nationality bars, the U.S. Department of Justice does not simply give up. Instead, prosecutors and diplomats employ an array of workarounds designed to ensure accountability. Four stand out.

- Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs).

Even when nationals cannot be surrendered, countries are often willing to share evidence. Through MLATs, U.S. prosecutors request bank records, witness statements, and other evidence to build cases in U.S. courts. These requests can also support domestic prosecutions in the haven country. By cooperating on evidence, the U.S. ensures that the fugitive is not beyond reach, even if they remain beyond the reach of extradition. - Encouraging Domestic Prosecution.

Many countries with nationality bars agree to prosecute their own citizens domestically for crimes committed abroad, provided the evidence is provided. Germany frequently does so, applying its own laws to U.S.-based offenses. In practice, this means that a German citizen accused of hacking U.S. companies may be tried in a German court. Sentences may differ, but accountability is achieved. For the DOJ, convincing foreign governments to prosecute is often a practical compromise. - Indictments in Absentia and Asset Freezes.

When surrender is impossible, U.S. prosecutors proceed with indictments in absentia, freezing assets and limiting fugitives’ ability to travel or conduct business. These measures ensure that while fugitives may remain free at home, their international movements and financial activities are closely monitored and constrained. Over time, this pressure can yield results, either by forcing cooperation or by incentivizing domestic prosecution. - Leveraging Interpol and Travel Restrictions.

Interpol Red Notices extend the reach of U.S. warrants across 196 member countries. While safe havens may ignore them, fugitives who travel abroad risk arrest. By limiting mobility, Red Notices turn nationality bars into gilded cages. Defendants may live openly in their home country but remain effectively trapped within its borders. For global businesspeople, this restriction can be crippling.

Case Study: Roman Polanski

Few cases illustrate the complexities of nationality bars better than that of Roman Polanski. The film director fled the U.S. in 1978 after pleading guilty to unlawful sex with a minor. For decades, he lived in France, which refused to extradite him as a French national. Attempts to arrest him abroad, including in Switzerland in 2009, failed due to technical flaws or political concerns.

The case infuriated U.S. prosecutors, who continued to pursue Polanski through diplomatic and legal channels. France’s nationality bar effectively shielded him, turning him into one of the most enduring symbols of extradition’s limits. For critics, the case proved that fame and nationality can combine to create impunity. For defenders, it underscored the importance of protecting citizens from foreign legal systems viewed as overreaching.

Case Study: Edward Snowden

Edward Snowden’s flight to Russia in 2013, following the leak of classified information about U.S. surveillance programs, highlighted how nationality bars intersect with geopolitics. Russia’s constitution prohibits the extradition of its citizens, and although Snowden is an American, Moscow granted him asylum and later granted him permanent residency.

Russian officials repeatedly declared that they would not extradite him under any circumstances, framing his case as political persecution. For the U.S., the refusal underscored how nationality bars blend with broader diplomatic disputes. Snowden remains in Russia to this day, a living example of how safe havens can protect fugitives when extradition is politically untenable.

Case Study: Brazilian Drug Traffickers

Brazil has applied its nationality bar in multiple narcotics cases. When U.S. prosecutors sought the extradition of Brazilian nationals accused of shipping cocaine into American ports, Brazilian courts blocked the requests. Instead, the suspects were prosecuted domestically under Brazilian law. Sentences were often shorter than those available under U.S. statutes, frustrating American officials but satisfying Brazilian constitutional requirements. The cases demonstrated both the effectiveness and the limitations of domestic prosecution. While accountability was achieved, the deterrent effect and restitution for U.S. victims were diminished.

Case Study: The German Hacker

In 2015, U.S. prosecutors indicted a German citizen accused of leading a cybercrime ring that stole millions from American banks. German law prohibited his extradition, but prosecutors in Munich pursued the case domestically after receiving evidence through an MLAT. The defendant was convicted and sentenced under German cybercrime statutes. While the sentence was lighter than what U.S. courts might have imposed, the prosecution avoided impunity. For the DOJ, the case demonstrated the value of evidence-sharing and the importance of encouraging domestic accountability when extradition is blocked.

Dual Nationality and the Extradition Dilemma

An increasingly complex dimension of nationality bars involves dual citizens. Many countries interpret their nationality laws broadly, refusing to extradite dual nationals if one of their passports is from a domestic country. For example, a Brazilian–U.S. dual national residing in São Paulo may be protected by Brazil’s constitution, even though the other nationality is American.

This creates unique challenges for the DOJ. Courts in Europe, too, have sometimes extended protections to dual nationals, ruling that surrendering them would violate the principle of equal treatment of citizens. Conversely, some states, such as the United Kingdom, limit the scope of nationality protections for dual nationals, applying bars more narrowly. For fugitives, dual nationality can be both a shield and a trap, depending on where they reside.

Recent 2024–2025 DOJ Cases Involving Nationality Bars

In 2024, U.S. prosecutors sought the extradition of a Brazilian-American dual national accused of leading a cryptocurrency fraud scheme that defrauded investors of more than $400 million. Brazilian courts refused extradition, citing constitutional protections. Instead, Brazilian authorities initiated domestic prosecution after receiving thousands of pages of evidence from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the DOJ. While American victims expressed frustration, the outcome illustrated how domestic prosecution functions as a compromise.

In 2025, German courts declined to extradite a German citizen accused of violating U.S. sanctions against Iran. Instead, the defendant faced trial in Frankfurt. Though the sentence was significantly lighter than U.S. guidelines, the case highlighted Germany’s willingness to uphold nationality bars while still pursuing accountability. The DOJ issued statements praising cooperation while acknowledging the limits imposed by nationality.

European Union Comparisons: The European Arrest Warrant

Within the European Union, nationality bars have been softened by the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) system. The EAW allows for near-automatic surrender between member states, with nationality providing fewer protections than in traditional extradition treaties. However, even under the EAW, some member states retain the option of trying their citizens domestically rather than surrendering them.

For example, Germany often chooses to prosecute domestically when another EU country requests the extradition of a German citizen. The EAW therefore represents a partial erosion of nationality bars, but not their full elimination. For the U.S., which is outside the EU framework, these reforms highlight both possibilities and limits. While Europe has moved toward efficiency, nationality remains a sticking point even among close allies.

Diplomatic Costs and Negotiation

Nationality bars are not just legal barriers; they are diplomatic flashpoints. When countries refuse to extradite citizens, Washington must decide whether to press the issue or accept domestic prosecution. Pressing too hard risks damaging alliances, while acquiescing may frustrate victims. Diplomats often frame nationality bars as matters of constitutional sovereignty, beyond negotiation.

Yet behind the scenes, quiet deals are struck. In some cases, the U.S. agrees not to press for extradition in exchange for assurances of domestic prosecution. In others, asset freezes or trade negotiations provide leverage. The balance is delicate: pushing too far can backfire, but failing to act can encourage fugitives to exploit safe havens.

Human Rights and Sovereignty Arguments

Defendants and their lawyers frequently invoke nationality bars in conjunction with human rights concerns. They argue that extradition would subject citizens to harsher penalties, unfair trials, or prison conditions abroad. Courts in Europe often accept these arguments, particularly when the U.S. seeks life sentences without parole or enhanced punishments. Sovereignty is another recurring theme.

Governments argue that protecting citizens from foreign courts is a matter of national dignity. These arguments resonate domestically, where public opinion often supports shielding nationals from foreign prosecution. For the U.S., this combination of legal principle and political sentiment creates a formidable barrier.

U.S. Strategies Moving Forward

The Department of Justice continues to refine its strategies in response to nationality bars. Prosecutors are increasingly proactive in preparing evidence packages tailored for foreign courts, anticipating domestic prosecutions that may occur abroad. Asset forfeiture and financial sanctions remain key tools, ensuring that fugitives cannot benefit from crime even if they stay beyond reach. The DOJ also works through diplomatic channels, pressing for treaty renegotiations or supplementary agreements that soften nationality bars. While success is limited, incremental progress has been achieved in some regions. The underlying goal is simple: to ensure that fugitives face accountability somewhere, even if not in the United States.

Implications for Businesses and Expatriates

For global businesses, expatriates, and professionals, nationality bars highlight the uneven landscape of extradition. A dual national may face very different risks depending on which passport they hold and where they reside. For example, a U.S.–Brazilian dual citizen may be safe from extradition while in Brazil but at risk abroad.

Executives operating in multiple jurisdictions must understand how nationality affects exposure to U.S. investigations. Compliance frameworks, travel planning, and risk assessments are essential. For individuals, nationality bars may appear protective, but they also carry costs: restricted mobility, constant surveillance, and reputational damage. Safe havens are rarely as secure as they seem.

Conclusion

Nationality bars represent one of the most enduring and politically charged challenges in the field of extradition law. They reflect sovereignty, loyalty, and constitutional principle, but they also create safe havens for fugitives. The United States employs creative workarounds, including mutual legal assistance, asset freezes, domestic prosecutions, and diplomatic negotiations, to address these issues. Case studies from France, Russia, Brazil, and Germany illustrate both the obstacles and the strategies employed to address these issues.

Recent cases in 2024 and 2025 demonstrate how dual nationality further complicates matters. European reforms under the Arrest Warrant system demonstrate how some barriers can be reduced, though not eliminated. For fugitives, nationality bars may offer temporary shelter; for victims, they represent delay and frustration; for governments, they are tests of law, diplomacy, and resolve.

As globalization deepens and cross-border crime expands, nationality bars will remain a defining feature of the extradition landscape, shaping who can be brought to justice and who remains beyond reach.

Contact Information

Phone: +1 (604) 200-5402

Signal: 604-353-4942

Telegram: 604-353-4942

Email: info@amicusint.ca

Website: www.amicusint.ca